There’s a trope I keep coming across more and more often in reviews lately, particularly photography-related reviews. I’m sure you’ve seen it plenty of times, too:

“This [camera/lens or whatever] is special because it inspires me to go out more and take better pictures.”

I mean, where to begin?

Let’s start with the obvious: whatever it is you’re reading about, it has nothing to do with your inspiration. It really, really doesn’t.

Inspiration and gear are so unrelated it really pains me to write this. Every time we read something like that and nod in enthusiastic agreement, we become willing victims of the greatest marketing hoax in the history of technology — and there have been quite a few.

To be clear, I’m as guilty of this as anyone, which is particularly disheartening because even knowing I’m being tricked, I still fall for it hook, line and sinker sometimes. Not always — let me at least preserve some dignity — but sometimes. That’s how powerful and alluring the marketing machine can be.

Take the latest example in the photography world: the introduction of the new and supposedly revolutionary Sony A7R Mark II camera.1

I say supposedly because the truth is, nothing is truly revolutionary in the photography industry anymore. Nothing can really be revolutionary in a discipline we mastered quite a few decades ago, unless we recently discovered some new laws of Physics I’m not aware of.

At the end of the day, the primary purpose of a camera is taking pictures — with the exception of videographers, but that’s a different story altogether. Anything that isn’t essential to the mission of taking pictures falls squarely within the “bells and whistles” category as far as I’m concerned.

Of course, bells and whistles are still important and if you’re going to buy a camera, they’re things you definitely need to consider.

Higher resolution? Great. Sharper lenses? Sure. Better dynamic range? Have at it. Longer battery life? Of course. Built-in WiFi? Awesome. Those are all pretty substantial improvements that are definitely nice to have in a modern camera. As for revolutionary? Not so much.

How much resolution and sharpness is nice to have? All we can get, clearly. How much is actually needed in the kind of photography that you do? Probably about 30-40% of your current camera’s specs.

I’m making it sound terrible, but this is actually great news. It means your equipment isn’t holding you back, creatively speaking. It never was, and it probably never will, so stop pretending you can’t take good pictures unless you spend $3,000 on a high-end “pro” camera.

Next time you get gear anxiety, think of it like this: people have been complaining about their photography gear for ages, and will remain doing so forever. And yet, people have also been taking breathtaking pictures for ages, and will remain doing so forever.

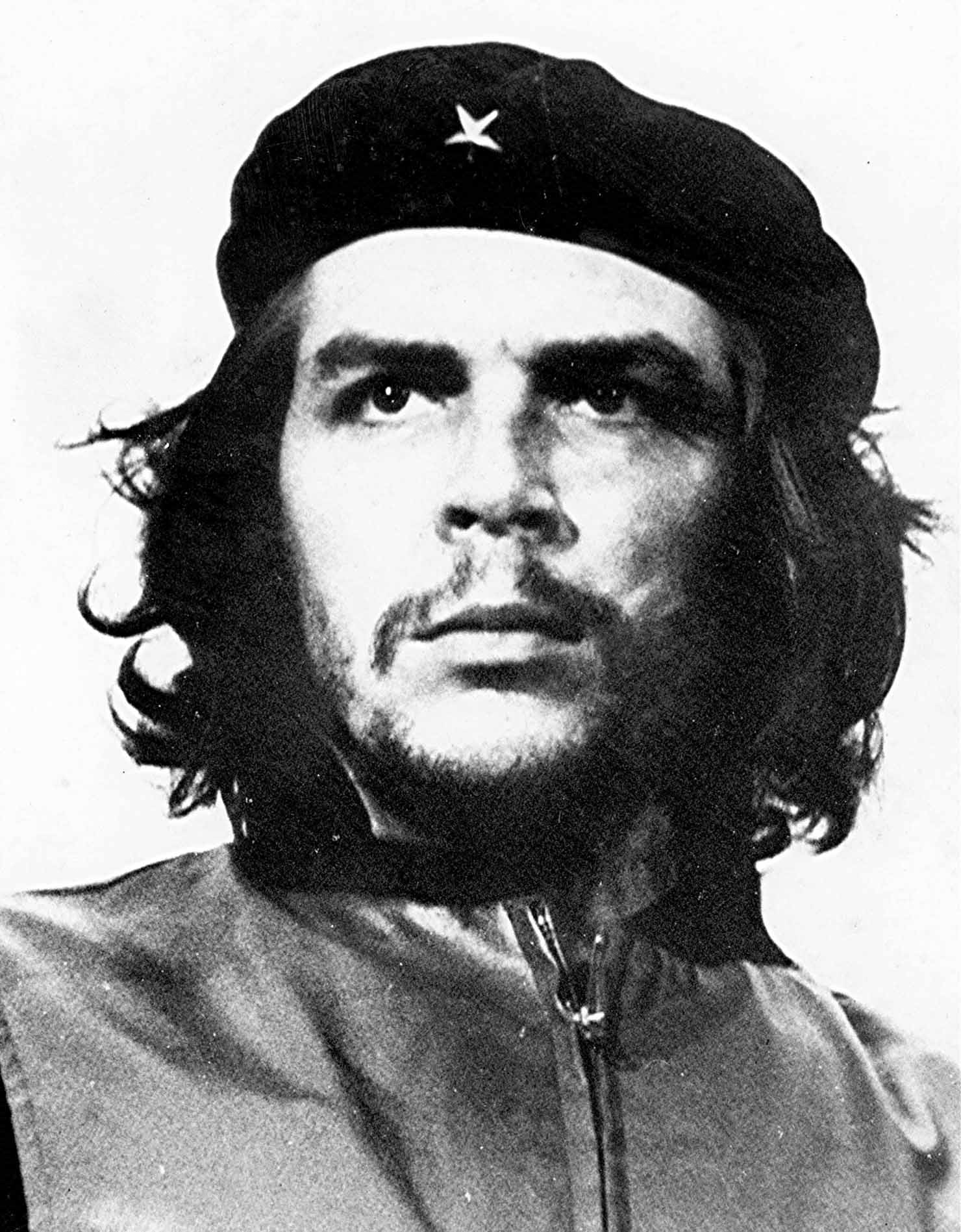

A vast majority of the greatest, most iconic images in history were captured by cameras with laughable specs by today’s standards, and you know what? Nobody cares. I’m yet to meet a person that looks at Ernesto Che Guevara’s iconic portrait and complains because it isn’t sharp enough.

“Guerrillero Heroico”. Ernesto Che Guevara at the funeral for the victims of the La Coubre explosion. Photo by Alberto Korda, 1960. Image is in the Public Domain.

Again, nobody cares about sharpness or specs. All people care about is whether the images themselves are compelling and in this case, I don’t think there’s any doubt. This goes to show there are many, many ways to create compelling images that don’t require owning the latest gear.

Style vs substance

Whenever I discover new artists whose work I love, I feel a natural impulse to peek behind the curtain. I want to learn everything about their creative process and the tools they use to create the work I so love. At that point, one of two things will happen: either I’ll find out that they use the latest and greatest technology, or I’ll find out that they’ve managed to excel at their craft using merely average tools. In some cases, really average tools.

I don’t know about you but more often than not, I tend to prefer the work of those who use average tools. In most cases, those artists somehow manage to create even more soulful, more authentic work. Check out this 16-year-old kid who’s capturing incredible macro shots in his backyard with the cheapest lens there is. Or some of the most respected and renowned artists in history, who got by using centuries-old technology, simply because it’s all that was available to them.

It goes beyond photography, of course. Do you really believe Michelangelo’s David would be any better if he’d used today’s technology to create it?

“David” by Michelangelo, 1501-1504. Photo by Jörg Bittner Unna, 2011. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

I didn’t think so.

Relying on technology to inspire us is missing the point entirely. Better tools are conducive to better output only up to a certain point and in many cases, that point was met a long, long time ago. But that’s only part of the issue.

The real problem is when people try to use technology as a shortcut to avoid learning a new craft.

Skill without discipline

The uncomfortable truth is, most creative disciplines require work. There’s always a learning curve and, until you’ve put in the hours, you won’t be able to grow as a creative person in a meaningful way.

Technology can help, but it’ll only take you so far. Indeed, and going back to the photography example, many popular features in modern cameras are entirely predicated on the notion of removing the need for knowledge and experience in photography. Features like Olympus’s Live Composite Mode completely eliminate the need for the user to know anything about creating long exposures in-camera.

That’s great if you only ever plan to shoot with Olympus cameras and it’ll definitely allow you to capture some gorgeous images but at the end of the day, you haven’t learned anything, and it hasn’t made you a better photographer because it didn’t take any effort or knowledge on your part.

Worst of all, technology can cheapen the end result. If all it takes to capture a scintillating long exposure is pressing a button, where’s the artistic merit? How is that image compelling in any way?

When you let the machine do the work for you, you’re giving up before the struggle’s even begun.

That’s not to say that you should never use technology in your creative work, of course. Many photographers would kill to have Live Composite Mode in their cameras, but the difference is they already know how to work without it. They have the discipline to know when to use it, and more importantly, when not to.

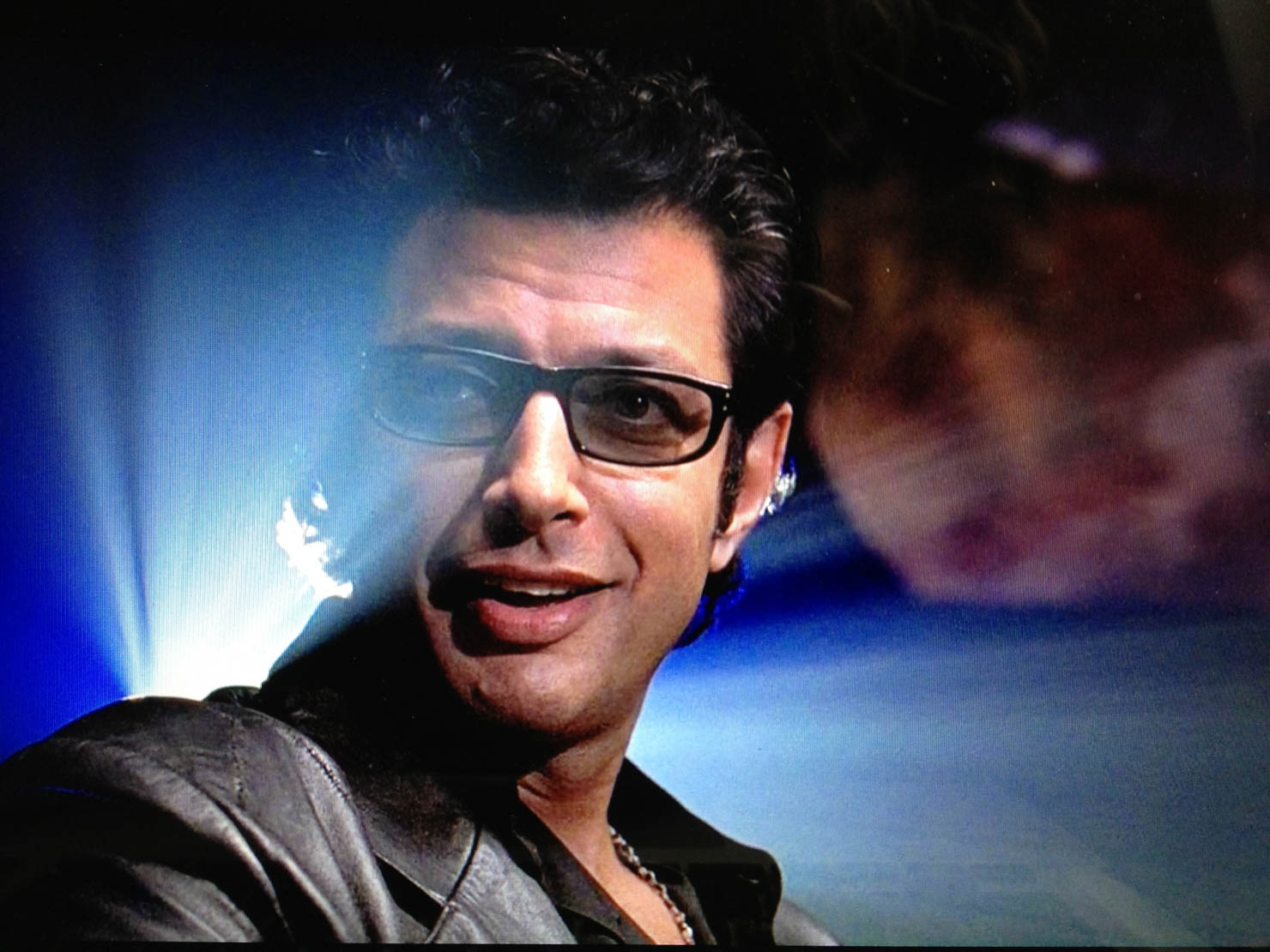

In the words of everyone’s favorite mathematician and chaos theorist, Dr. Ian Malcolm:

Most kinds of power require a substantial sacrifice by whoever wants the power. There is an apprenticeship, a discipline lasting many years. Whatever kind of power you want. President of the company. Black belt in karate. Spiritual guru. Whatever it is you seek, you have to put in the time, the practice, the effort. You must give up a lot to get it. It has to be very important to you. And once you have attained it, it’s your power. It can’t be given away: it resides in you. It is literally the result of your discipline.

Now what is interesting about this process is that, by the time someone has acquired the ability to kill with his bare hands, he has also matured to the point where he won’t use it unwisely. So that kind of power has a built-in control. The discipline of getting the power changes you so that you won’t abuse it.

That is exactly my point. Technology can be a powerful enabler, as it allows people to attain knowledge without discipline. Sometimes that’s great, but sometimes it’s unfortunate. You should definitely use technology as an aid, but not as a substitute for experience.

Dr. Ian Malcolm as portrayed by actor Jeff Goldblum in the film Jurassic Park, 1993.

Now, it’s not all bad, of course. Sometimes technology enables us to achieve things that were previously impossible and in those cases, by all means, go ahead and use it. Go nuts. But even then, I suspect it’ll be the people with previously attained knowledge and discipline who will be the most apt at exploiting it to its full potential.

Simply put, there’s no substitute for doing the work.

Taking the long road

Despite what many will tell you, technology can’t make you better at anything if you refuse to do the work. You can buy Roger Federer’s racquet, but that won’t make you any more of a tennis player. You can buy the Sony A7R II, but that won’t make you a better photographer.

Chances are, the tools you currently own are far more capable than you are to produce great work. By refusing to earn the discipline it takes to explore them to their full potential, you’re only keeping yourself from growing as a creative person.

Stop making excuses. Stop acting as though the lackluster quality of your work is the world’s fault. “If only I had a better camera” only fools yourself.

Experience needs to be earned, and technology is no substitute for it. It’ll take discipline, hard work and yes, time, but if you’re determined to do it, half the battle is already won.

The other half is up to you.